Colonel Arthur L. Kelly, USA (Ret)

On Sunday morning June 25, 1950, Kentuckians had their regularly scheduled radio program interrupted for a newsbreak. The commentator announced that the Communist North Korean Army had invaded South Korea. Following the United Nations (UN) decision to resist aggression and the imminent defeat of the poorly equipped and badly battered South Korean Army, Task Force Smith, an Infantry Battalion (plus) from the U.S. 24th Infantry Division, was sent in from Japan to delay the enemy. As other forces were being scraped together and rushed in, Task Force Smith was quickly overrun near Osan by the North Korean army equipped with Russian tanks. Suffering heavy causalities, as the other forces were thrown in by piece meal commitment, General Walker hung on desperately by delaying actions and bought enough time to establish the hard pressed Pusan Perimeter. Kentuckians remembering Bataan rightly worried about their sons being driven into the sea.

However, by Sept 15, 1950, General MacArthur, against the advise of everyone, made his famous and great turning maneuver by landing an Amphibious Force at Inchon. Following the Pusan Perimeter break-out and link-up with the Amphibious Forces, and following the nationally heated debate on how to limit the war, MacArthur sent Gen. Walker’s 8th Army and Gen. Almond’s separate X (10th) Corps on a rapid pursuit of the enemy. The UN forces were so widely scattered that by the time some units reached the Northern boundary of North Korea and over-looked the Yalu River, China had infiltrated Army Groups between the UN Forces.

On November 25, 1950, the Chinese Red Armies surprised and attacked the UN Forces in mass and while inflicting heavy casualties sent the UN forces reeling southward to a defensive line south of Seoul. By July 1951 after both sides alternated between the defense and offense mostly just north of Seoul, the lines stabilized generally just north of the 38th Parallel. Then for the next year and a half the war became a war of "position," similar to the trench warfare of WWI. While bitter negotiations continued at Kaesong and Panmunjom, the front lines became bunkered in with connecting and fighting trenches. Both sides then conducted limited offensive actions known as, "The Battles For The Hills" until the war ended July 27, 1953.

That was the condition in Korea Dec. 23, 1951, when the 623rd Field Artillery Battalion arrived with its eighteen 155 MM Howitzers. The 623rd was Kentucky’s only National Guard unit to serve in Korea. The Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, A, B, C, and Service Batteries were from; Glasgow, Tompkinsville, Campbellsville, Monticello, and Springfield.

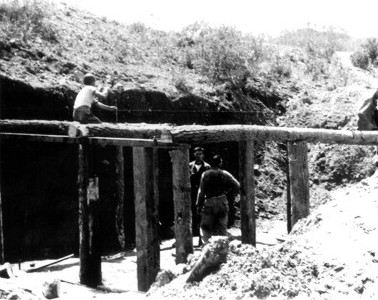

For a while in their first position in the Mungdung-ni valley all the artillery was what the troops called "outgoing." Nevertheless, Lieutenant Fred Rankin, C Battery’s executive officer from Monticello, insisted on the troops building live-in bunkers. In June 1952 when the valley received "in coming" intense enemy artillery fire, the protection provided by the bunkers rewarded the troops for their hard labor. The logs shown in the picture were dragged out of the mountains with the howitzers prime-movers. The logs on top of the bunkers were covered with two or three layers of sand bags plus three feet of dirt. Later when the rainy season came that bunker was swept off the hill in a landslide. Fortunately, the bunker popped and cracked before it collapsed allowing the occupants time to scramble out.

The logs shown in the picture were dragged out of the mountains with the howitzers prime-movers.

While in that position, the Kentuckians underwent a cultural shock when they learned that they’d be included in The Army’s decision to integrate its units. Soon black and white soldiers; worked, ate, played, and laughed together; used the same facilities; slept in the same bunkers; and became friends. Integration in the 623rd went well.

When the 623rd moved in July 1952 to its second position in Smoke Valley near the Punch Bowl, the bunkers were positioned to avoid a land slide (In the photograph below: SFC Cullem Coffey, from Monticello, is 3rd from the left). That was an unusual position. Headquarters and the three firing batteries were tightly clustered. Smoke generators operated in front of the units during daylight hours to block enemy observation of the battalion. Incoming artillery fires were received in Smoke Valley.

SFC Cullem Coffey, from Monticello, is 3rd from the left

By the time the 623rd moved to its third position north of Seoul and south of Panmunjom in October 1952, the Batteries had become skilled bunker builders. When a Lieutenant, from Missouri, in B Battery was killed by incoming rounds shortly after the Battalion arrived at the 3rd position, Lieutenant Arthur L. Kelly, Battery A’s new executive officer, from Springfield Kentucky took a convoy of trucks and went on a scrounging mission to get materials to build bunkers.

Despite being lectured on proper supply procedures at some supply depots, Lieutenant Kelly returned with his trucks loaded to the brim with heavy and light building materials. He traded a load of lumber to the nearest Marine Artillery unit for the use of their bulldozer. In less than a week, Battery A was living in the finest bunkers in Korea. As word spread around about the quality of the bunkers men from other units far and wide came to see them.

Lieutenant Arthur L. Kelly, Battery A’s new executive officer, from Springfield Kentucky (In the Photograph he has the pipe in his mouth)

Battery A had nine bunkers 12 feet by 24 feet and one odd shaped bunker for the Fire direction center (the nerve center of the Battery).

There was one bunker behind each of the six howitzers for the gun crews (12 men), two for the Headquarters section and one for the Officers. Over the bunker’s roofs and one leg of the L shaped entrances were 2 layers of sand bags filed with dirt one foot of loose dirt, layers of rocks, to stop enemy artillery rounds with a delayed fuse, and then more dirt. Unlike the other two sets of bunkers these bunkers were water proofed and drained with a pumping system made out of empty powder canisters gotten from a neighboring 8-inch artillery unit. This third set of bunkers were ventilated, dry, lighted with electricity, and comfortable. There was no mildew, snakes, or rats in these bunkers.

From left to right: Captain Albert Loy (C Battery) from Columbia, Ky.; Lt. James May (A Battery not a member of the National Guard); Captain Oran Billingsly (B Battery) from Tompkinsville, Ky.; Colonel Whitehouse had taken Command of the Battalion from Major Edward H. Milburn, of Springfield, Ky., who had finished his tour.

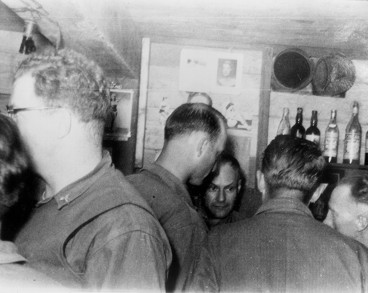

At a going home party Lieutenant Colonel Haydin Whitehouse, from Oklahoma, was pleasantly surprised when he ordered a martini as he entered, for the first time, Battery A’s Officer’s Bunker and learned he would get one. Lieutenant Kelly had acquired the bar-drinks from the British. Colonel Whitehouse is facing the three bring Battery Commanders in the photo. The individuals are from left to right: Captain Albert Loy (C Battery) from Columbia, Ky.; Lt. James May (A Battery not a member of the National Guard); Captain Oran Billingsly (B Battery) from Tompkinsville, Ky.; Colonel Whitehouse had taken Command of the Battalion from Major Edward H. Milburn, of Springfield, Ky., who had finished his tour.

The 623rd Field Artillery Battalion became a premier artillery battalion in Korea. Its National Guard officers had been commissioned in a variety of branches and many of them had seen combat in WWII. This gave the Battalion a breadth of military and leadership skills. However, their artillery training while in the National Guard from 1947 to January 1951 had been limited. However, following their entry on active duty, January 23, 1951, the officers were sent from Fort Bragg, on a rotational basis, to Fort Sill Oklahoma for their artillery schooling. This coupled with intense training at Fort Bragg gave them a depth of artillery skills.

Bunker Photo 4

The Non-Commissioned Officers were the best. Many were WWII veterans. The Artillery Group S-1 (personnel officer) at Fort Bragg said that he had never seen so many men from one battalion qualified for officer’s candidate school. The filler personnel (about 35 percent) were draftees mostly from Wisconsin, Ohio, and Indiana. They were a fine group of young men. With this mixture of personnel and firing artillery missions often both day and night in Korea, the units soon became so proficient, that watching the crews in action was like watching a well-oiled machine.

Following a mission fired by Battery C while located in the Mungdung-ni valley, the Corps Artillery Aerial Observer drove several miles from the airfield to congratulate the men for a job well done. He told them that he had never seen any unit fire as fast and as accurate as they had just done. Later Lieutenant General Palmer, the X Corps Commander visited the unit in the same location to congratulate them for having scored the highest score of all the Corps Artillery units on the recently administered Battery Test.

Bunker Photo 5

When the Marines came under heavy attack in October 1952 in the area known as the "Hook," the 623rd answered their calls for artillery support. After the bloody battle, the Marines said it was the best artillery support that they had ever seen. For its outstanding fire support while in General Support of the Marines and two Korean Divisions, The 623rd FA BN was awarded the Navy unit commendation medal and the Republic of Korea Unit citation medal.