1776 was a significant date in the growth of the Kentucky Militia in that George Rogers Clark, with others, represented Fincastle County before the Virginia Assembly. Due to the efforts of these men, 500 pounds of gunpowder were granted for the young Militia to use in defending its settlement against the Indians. It was during this same year that the Virginia Assembly trisected Fincastle County, with one of the sections being designated as Kentucky County. As the result of this division, Kentucky County was accorded its own separate and distinct Militia, which was sorely needed to repel the numerous Indian raids on such places as Logansport, Harrodsburg, and Boonesboro. Officers of this newly created Militia district included such significant historical figures as Daniel Boone, who was commissioned by the Assembly to command Boonesboro.

During the Revolutionary War few British troops came into Kentucky. But the young Militia faced a far more formidable, dangerous force than the British in that Indians working as mercenaries were paid by the British for the number of Kentucky scalps collected. One of the more notable operations that the Kentucky militiamen participated in during the War for Independence was the successful raid led by George Rogers Clark against the Indian outposts at Kaskaskia and St. Vincents (Vincennes). In 1774 with the creation of the Provisional Congress in 1774 the Committee of Safety instituted non-loyalist commissions to fill vacancies in the loosely organized home guard.

Painting of the Battle of Blue Licks

In 1780, the efficiency and organization of the Kentucky State Militia were further achieved when the Virginia Assembly divided Kentucky County into Fayette, Jefferson, and Lincoln counties, each of which had its own Militia. It is interesting to note that Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Boone was at this time commissioned to command the Lincoln County Troops.

The supreme test of the early frontier Minutemen occurred in Fayette County when approximately 500 Indians attacked Bryan Station. This raid was repelled chiefly by the Kentucky garrison who stayed under cover and the sharp-shooting militiamen who inflicted fatal fire on any Indian that showed himself. The delay discouraged the attackers, who evidently feared that by prolonging their siege they would subject themselves to the fire of reinforcements that were certain to arrive. Militia from around the area converged on Bryan Station. Finding the attackers had withdrawn, a council was immediately held by the officers, where it was decided to give chase to the Indians. Early on the morning of August 19, 1782, the Militia arrived at the south bank of the Licking River near the Blue Licks salt springs. The Indian army lay hidden in a series of wooden ravines at the crest of a hill. As the Militia assembled on south bank of the river a group of warriors, serving as decoys, appeared in plain view on the hilltop. Another officers' council was called, Daniel Boone urged caution; he pointed out things he had noticed on the march and suggested the possibility of an ambush by the Indians. "They intend to fight," Boone said. Hugh McCary grew angry and defiant. "Them that ain't cowards follow me," he shouted leading a general charge across the river directly into the ambush and hand-to-hand fighting that followed. The result was disaster for the Kentucky Militia and a resounding victory for the Indian/British force. Seventy-two Kentuckians were killed in the fight; more than a third of their force. The Indian and British lost only three men and four more slightly wounded. The Battle of Blue Licks occurred ten months after General Cornwallis had surrendered at Yorktown and would go down in history as the last battle of the American Revolution.

In 1783 George Washington prepared the workings for a "Militia of the Continent" which was to be constituted of citizen soldiers responsible to the Federal government in time of national emergency.

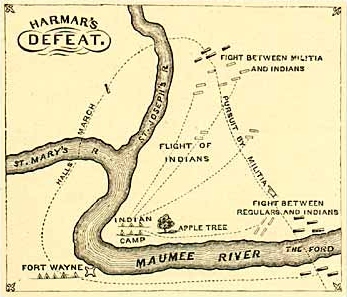

After the close of the Revolutionary War the Militia was given a brief respite from Indian hostilities. Unlike her Eastern and northeastern sister states, however, Kentucky was still exposed to dangers initiated by the British who had refused to surrender their post in the Northwest. The British used their position to incite the Indians by offering bounties for scalps of Kentucky prisoners. This meant that the Kentucky Militia had to remain organized in constant vigilance against such hostile attacks. Court records of Jefferson County indicate the importance of the Kentucky Militia in the 1790's. Generals' Harmar and St. Clair led militia and federal troops in defense of the Northwest Territory north of the Ohio River. It was in this context that in 1791 that the worse defeat ever visited upon United States military by the Indians took place on the Wabash River in Ohio. Many Kentuckians were among the 1,000 men and two batteries of artillery lost to the Indians. The brother of Kentucky Adjutant General Butler was among those slain.

"Death of General Richard Butler" Painting By Hal Sherman

"Death of General Richard Butler" or "Butler's Demise" 1791 at the battle of St. Clair's Defeat painted by Hal Sherman of Englewood, Ohio. Butler County Kentucky, is named in honor of Richard Butler (April 1, 1743 - November 4, 1791) who was an officer in the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War and saw action at the Battle of Saratoga and the Battle of Monmouth along with his four brothers and all were noted for their bravery.

Richard Butler was second in command in an expedition led by General Arthur St. Clair against Indians. Brothers Thomas and Edward were also in the company. On the morning of November 4, 1791, Indians led by Chief Little Turtle ambushed the army and killed 600 men and scores of women and children in the Battle of the Wabash, also known as St. Claire's Defeat. Richard Butler was killed with a tomahawk blow to the head. Painting used with permission and info submitted by Hal Sherman.